- Category

- Client Alerts

- Date

- Oct. 13, 2021

- Title

-

Contractual Tensions in the Context of Post-COVID Economic Recovery: Legal Tools and Guidelines

After a year and a half of a global pandemic, INSEE (French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies) announced on Sept. 7 a forecast growth of 6.25% of French GDP, thanks in particular to household consumption.

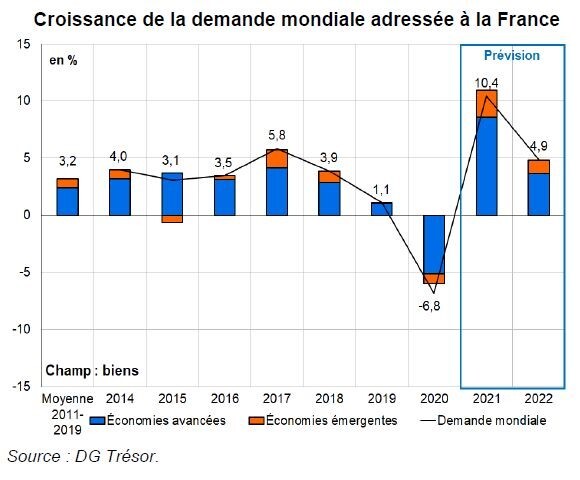

On the same day, the French treasury presented the outlook for the French economy in the second half of 2021 and over the year 2022 (see chart below).[1]

The accelerated recovery of economic activity after (or with) COVID is causing significant economic — and therefore contractual — tensions.

Economic actors are facing difficulties of various natures, impacting their commercial relations:

- Mainly, the supply of raw materials, whose sourcing has been slowed down, even stopped during the year 2020, is not yet back to normal, while the world demand is exploding (for copper, iron, steel, aluminium, wheat, wood, oil, etc.). As a result, the price of raw materials is increasing exponentially and suppliers are forced to announce shortages of raw materials or primary components.

- Production difficulties have added to supply difficulties. The health crisis has destroyed jobs, and the necessary recruitment combined with the reorganization of human resources is also limiting production capacity in certain sectors.

- Finally, companies are experiencing difficulties in transporting products and goods due to increased demand in some parts of the world, and are exposed to a corresponding increase in the cost of freight and, for the customer, of goods.

In such circumstances, economic actors strive to respect their contractual commitments and risk liability for breach of contractual obligations, or even for the brutal rupture of commercial relations.

Which legal tools to rely upon to avoid or limit contractual liability?

The concepts of force majeure and unforeseeability are heavily being relied upon. However, it is possible to use other legal grounds, such as significant imbalance between the parties, or to use sliding scale, take-or-pay or make-or-pay clauses.

Force majeure — Force majeure releases the person who is no longer able to fulfil his obligation. The new formulation of the definition of force majeure seems to have slightly softened the requirements of unforeseeability and irresistibility.[2]

Furthermore, the courts also accept the contractual arrangement of the concept of force majeure, provided that a certain amount of unforeseeability remains. The effectiveness of force majeure clauses depends on their wording, which must be carefully drafted.

Mainly, clauses that list, by way of illustration and not exhaustively, the events that will constitute force majeure do not exempt the defendant from proving that the conditions of force majeure — unforeseeability, irresistibility and exteriority — are met. By way of illustration, the Paris Court of Appeal ruled that a clause providing that “by express agreement between the parties, all natural phenomena, such as storms, thunderstorms and cyclones, etc., are considered to be cases of force majeure, exonerating the service provider from all liability” does not deprive the judge of his or her power to assess the unforeseeability and irresistibility of the event.[3] A reference in the force majeure clause to a supply shortage or pandemic does not necessarily relieve the party invoking it from establishing the conditions of force majeure.

Conversely, clauses that provide that the events in question are to be treated as force majeure, regardless of the legal requirements of exteriority and irresistibility, exempt the parties from proving that the conditions of force majeure are satisfied. In order to broaden the definition of force majeure, these clauses may also mitigate the rigour of irresistibility. Total Direct Energie managed to avoid liability against EDF, based on the force majeure clause exonerating the parties in case of impossibility to perform “under reasonable economic conditions.”[4]

Force majeure clauses have already proved their efficiency in the context of the COVID crisis,[5] even though this efficiency might be nuanced given the ever-decreasing unpredictability.

The consequences of force majeure are radical, and it may be preferable to renegotiate the agreements, thus allowing the relationship to continue under new and more acceptable conditions.

Unpredictability (Article 1195) — The concept of unpredictability “rendering performance excessively onerous for a party who had not agreed to bear the risk”[6] seems to be especially relevant to situations of rapidly rising prices of raw materials or transportation.

The legal mechanism of renegotiation can, for example, enable the adjustment of the contract’s performance time frame, the waiver of late penalties or the revision of the price, either with the business partner, at best, or with the commercial court.

Beware, the occurrence of an “unforeseeable event” within the meaning of the law does not authorize the party to suspend the performance of its obligations. Article 1195 provides that “it shall continue to perform its obligations during the renegotiation.”

However, clauses waiving the provisions of Article 1195 of the Civil Code have proliferated for fear that the judge will be entrusted with the determination of the “fair price,” thereby precluding the right to renegotiate the contract. In the future, lawyers will certainly try to adjust the conditions and effects of unforeseeability rather than opt for its systematic exclusion.

For the time being, the effectiveness of these waiver clauses could be challenged on the basis of significant imbalance.

Significant imbalance in the contract — A waiver clause under Article 1195 of the Civil Code could be set aside if it is deemed to create a significant imbalance between the rights and obligations of the parties, on the basis of Article 1171 of the Civil Code or on the basis of Article L. 442-1 of the Commercial Code (which authorises a request for the clause to be declared null and void[7]), in particular where it places all the risks inherent in the performance of the contract on one party.

Regardless of the effectiveness of the waiver clause, the significant imbalance between the rights and obligations of the parties may justify compensation of the party bearing the alleged imbalance — and achieve the same result as a renegotiation of the price on the basis of unforeseeability — particularly where a contract provides for a long-term relationship and was not (or was only marginally) negotiated at the time of its conclusion and where there are nonreciprocal clauses.

Sliding scale clauses — Sliding scale clauses, or indexation clauses, which allow the price to vary automatically based on the fluctuation of a reference index (e.g., the price of wheat or oil), are also particularly useful in this post-COVID recovery phase. Their beneficiaries should not hesitate to rely on them as they merely reflect the intention of the parties at the outset.

Conversely, the resulting price increases could again make the performance of the contract particularly onerous for the purchaser of the good or service, who might then be tempted to invoke unforeseeability.

Commercial agreements sometimes provide for an upward price variation only and a price freeze in the event of a fall in the index. The Court of Cassation has ruled that such clauses must be reciprocal and that otherwise they are void.[8]

The indexation clause only protects against price variations. It is therefore recommended that it be accompanied by contractual mechanisms that protect the parties against the risks of nonperformance to a greater extent (for example, delays in supply) and, above all, that it be capped in order to avoid excessive price increases.

Take-or-pay/make-or-pay clauses — Supply disruptions should not overshadow the risk faced by suppliers that continue to make deliveries but are faced with customers’ refusal to pick up goods. Under take-or-pay clauses, a company is obliged to ensure the withdrawal of ordered products or, failing that, to pay a penalty.

Situations are diverse, and the use of specific levers must be adapted to the objective sought, the position of the client or supplier, and the extent of the disruption caused to economic actors after a recovery that is universally praised but whose strength is unprecedented.

[1] World outlook in autumn 2021: a heterogeneous catch-up | Direction générale du Trésor (economie.gouv.fr).

[2] Article 1218 of the Civil Code: “There is force majeure in contractual matters when an event beyond the control of the debtor, which could not reasonably be foreseen at the time of the conclusion of the contract and the effects of which cannot be avoided by appropriate measures, prevents the performance of his obligation by the debtor.”

[3] CA Paris, 28 Feb. 1990 : RTD civ. 1990, p. 669, obs. P. Jourdain.

[4] T. com. Paris, ref. order, 20 May 2020, n° 20201647 : JCP E 2020, 1350, note M. Lamoureux.

[5] See not. Rép. min. n° 28330 : JOAN, 25 August 2020, p. 5644.

[6] Article 1195 of the Civil Code: “If a change in circumstances unforeseeable at the time of the conclusion of the contract renders performance excessively onerous for a party who had not agreed to assume the risk, that party may request renegotiation of the contract from his co-contractor. It shall continue to perform its obligations during the renegotiation.

“If renegotiation is refused or fails, the parties may agree to terminate the contract, on the date and under the conditions they determine, or may ask the court, by mutual agreement, to adapt it. If no agreement is reached within a reasonable time, the court may, at the request of one of the parties, revise the contract or terminate it, on the date and under the conditions it determines.”

[7] C. com. L. 442-4, as amended by the Order of 24 April 2019.

[8] Court of Cassation — Civil Division 3, Public hearing of Thursday 14 January 2016, No. 14-24681.